Welcome The FISH story

As the Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery prepares to celebrate its 30th anniversary, we are taking a look back at the people and the activities that brought about the formation and development of this unique organization and partnership.

A special thank you to Grace Reamer for telling FISH’s story, interviewing our key founders & writing these important historical & cultural stories.

The science of salmon: more than a job for Mike Mahovlich

By Grace Reamer

Just two years into his new job in fisheries management with the Muckleshoot Tribe, Mike Mahovlich got a desperate phone call. It was Steve Bell from Issaquah on the line. News had just broken that the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife planned to close the historic Issaquah Salmon Hatchery. City officials, Chamber of Commerce members, students and citizen volunteers were mobilizing to save the hatchery. Would Mahovlich and the Tribe be able to help?

Immediately, Mahovlich realized the stakes involved. Without the Issaquah hatchery supporting survival of chinook and coho stocks in the Lake Washington basin, the runs would likely decline and disappear within a few years. By 1992, evidence of the environmental damage created by urban development was showing up in local waters.

“Especially in the Lake Washington watershed, we started to see things crashing with the sockeye run,” Mahovlich remembered. “At the same time, the state was giving up on the Issaquah hatchery.”

Now serving as assistant director of harvest management for the Muckleshoot Tribe, Mahovlich remembered those years in the early 1990s as the Tribe’s fisheries work expanded following the Boldt decision assuring tribal treaty rights to half of the harvestable fish runs. Tribal operations were very small then, but he started projects such as fry trapping in the Cedar River to assess survival rates as well as expanding the hand-counting of returning adult salmon at the Ballard Locks. Among all of the non-native predation, warm water conditions and pollution, the proposed closure of the Issaquah hatchery was a new threat to the Northwest’s iconic fish.

“You never walk away when things are bad; you do the exact opposite and dig your heels in,” Mahovlich said. “The Issaquah hatchery is the heart and soul of the chinook and coho runs for the whole Lake Washington basin.”

He jumped right into the Issaquah community effort to save the hatchery. “We had just a small group, but I knew I could get the Tribe involved at the policy level including a strong lobbying effort approved by the council,“ he said. With treaty rights to harvesting salmon throughout its historical fishing grounds, the Muckleshoot Tribe serves as a co-manager of the salmon runs and has a great interest in their survival.

“We told the state early on not only that the hatchery was not going away, but we were going to rebuild it better than ever for the salmon, both adults and juveniles, along with a very strong educational program, which hadn’t been done at any state facility. I got right into the middle and came up with the master plan in phases.”

Those phases – starting with replacing the migration-blocking weir, followed by a new fish ladder and holding ponds, then rearing ponds and a watershed science center – helped convince the state to maintain and rebuild the community and regional resource in Issaquah.

“The final powerful message that was being carried (to Olympia) was the need to start educating the public,” Mahovlich said. “That was a huge missing link at state hatcheries.” Because of Issaquah’s close proximity to a major urban area and its easy access in the middle of old town a short distance from I-5, the Issaquah hatchery was promoted as the best place in the state for public outreach about salmon and habitat conservation.

“It’s an investment into the next seven generations,” Mahovlich said, referring to the Native philosophy of managing natural resources so that descendants seven generations away will still benefit from the same environment. “We need to be not so short-sighted. The salmon habitat is not coming back.”

He said he believes that people can learn to live alongside fish while mitigating the habitat damage done by urban development.

“How do we make sure the cities embrace it? How do we keep the fish alive for the next seven generations?” he wondered. The rebuilt hatchery, combining fish culture with education, was the answer. “There should be sustainable, harvestable fish for everyone. You have to work with what you got in hand, and that is not much when it comes to salmon standards in this urban concrete jungle of a watershed. You can’t go to Target and buy a new watershed.”

As the hatchery promotion efforts heated up, Mahovlich moved from Seattle to Issaquah and joined the board of the newly formed Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery. For years, he helped steer the new non-profit agency as it developed education programs and solicited grants and donations. He trained volunteer recruits to interpret the salmon story and explain their biology, lifecycle and habitat needs to the many thousands of visitors arriving at the hatchery to view the annual migration spectacle.

“What I am most proud of when it comes to the education side of the hatchery is that the final rebuilding master plan incorporated my idea of putting in glass walls so all visitors could get race to face and inches away from these magnificent adult salmon,” Mahovlich said. “This is a learning experience for everyone young and old to enjoy.”

His passion for fish started very early in life, growing up in Coquitlam, B.C. and fishing for trout in his backyard stream. As a teenager, he turned to athletics and earned a scholarship to the University of Washington in track and field, where he threw the javelin. His prowess in the sport even earned him two trips to the Olympics with the Canadian team, and he continued to compete, working through an Achilles tendon injury, retiring in 1990 after the Commonwealth Games in Aukland, New Zealand.

After college, he returned to Canada and worked with the Pacific Salmon Commission and Department of Fisheries and Oceans in Vancouver, B.C. Eventually, he applied for a job with the Washington Department of Wildlife (before it merged with Fisheries). He was offered a volunteer position. Disappointed, he continued looking, and two weeks later, in the autumn of 1990, saw the posting for the Muckleshoot job. As he prepared to go in for his interview, he saw one of his college professors walk out ahead of him, and once again was prepared to be disappointed. Instead, he ended up as the 77th employee hired by the Tribe.

Thirty-four years later, he’s constantly called upon to develop policies and strategies in the ongoing efforts to save struggling salmon populations. As threatened Puget Sound chinook were experiencing pre-spawn mortality and not making it through the lakes and rivers to their spawning grounds, Mahovlich devised an experiment that transferred a few adult chinook from the Locks where they entered fresh water directly to the Issaquah hatchery. It worked.

Encouraged by the success, he proposed to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) extending it to the decimated sockeye run. In June of 2021, as Seattle experienced a heat dome and record high temperatures above 100 degrees, the co-managers started the transfer by dip-netting live sockeye at the Ballard locks fish ladder, placing them in a live tank on a boat, then hauling them to a Port of Seattle landing station. The fish then were loaded in truck tanks to drive to the Cedar River hatchery at Landsburg. They devised three different acclimation processes during the six-hour trip to help the fish adapt to the varying water temperatures.

Over the past three summers, the program moved more than 3,000 sockeye without one enroute mortality. All the fish made it to the hatchery safely and ripened in holding ponds over the next four months, finishing their life cycle with a very high spawning success rate. Now known as BLAST (Ballards Locks Adult Sockeye Transfer), the program has given the co-managers hope that the Tribe and local residents will again enjoy sockeye fisheries in Lake Washington where, a few years ago, it looked like extinction was likely to happen in the very near future.

Thanks to his work on partnerships with the Tribe, WDFW and non-profit organizations, other projects are making progress on protecting the Lake Sammamish kokanee as well as Cedar River sockeye through extended rearing of fry at the Issaquah hatchery and reducing non-native predators such as bass and perch. He pointed out that the importance of the work at the Issaquah hatchery extends well beyond the community and the watershed, because so many people and species depend on hatchery origin salmon, such as the Southern Resident Killer Whale (SRKW) or orca populations – the J, K and L pods – which prefer the large chinook salmon for food.

Mahovlich still mourns the loss of the steelhead run in the Lake Washington basin, which includes Lake Sammamish and the Issaquah Creek watershed. The Issaquah hatchery at one time raised steelhead to release into the watershed, but eventually, federally protected sea lions cornered the returning fish in tight quarters as they entered the fish ladder at the Ballard Locks, and ate most of them.

“I don’t want to lose another species on my watch,” he said.

The Original Fish Guide: Suzanne Suther

By Grace Reamer

For Suzanne Suther, her love affair with the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery all started about 50 years ago, when she was hired in 1974 as a step-on tour guide for a tourist bus tour company in Seattle. For the day-long tour, she had to learn quickly about the small-town sights in Woodinville, Snoqualmie and Issaquah, including Gilman Village, Boehm’s Chocolates and the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery.

As a gregarious and enthusiast guide, Suther learned the basics of the salmon life cycle and enchanted her tourists with stories of the amazing migration of the chinook and coho back to the stream of their birth. She already had history with fishing, after catching her first fish at age 10. She loved to share fishing stories, including the time she caught a 45-pound chinook. Her experience and passion were a perfect fit for her tour to the hatchery.

“Having done that, I became very, very, in love with the hatchery,” she remembered. People from all over the world joined her tours, and the salmon were “the thing they wanted to know about most. Their awe – that was all they talked about. That left a tremendous impression on me.”

But the hatchery back then was not a very welcoming place. The staff were not interested in talking to visitors. The bathrooms were locked. The trash cans were beat up and dirty. It was a fish production operation rather than a public park. Suther soon joined the board of the Issaquah Chamber of Commerce and worked on ways to improve the appearance of the hatchery. She made a deal with a local nursery for a large batch of geraniums, then planted the flowers around the hatchery grounds and got staff to agree to water them. That was just the beginning of her promotional and educational work.

She went as far as Olympia to get attention for the hatchery. On a trip back from visiting her sister in Portland, on a whim, she pulled off I-5 at the state Capitol and made her way to the state Fisheries Office. She asked to speak to someone about the Issaquah Hatchery. That’s how she met Will Ashcraft, a fisheries manager who happened to have started his career at the Issaquah hatchery. She talked to the sympathetic administrator about how the Issaquah facility, with its easily accessible location, could be used to promote salmon conservation. With a month, she remembered, the unaccommodating hatchery manager was transferred, and a new manager arrived carrying the mission to make connections with the community.

Back in the early 1970s, Issaquah was still a small town in the Cascade foothills, looking for a way to distinguish itself. The annual Labor Day Festival and Parade had just finished its decades-long run as the town’s main civic celebration. City leaders sought a new way to show their civic pride.

Members of the Chamber and the Kiwanis Club met to discuss what they could do to promote Issaquah, Suther remembered The Issaquah Press editorialized about the need for an effort to bring tourism to town to support the local economy. That soon led to the City of Issaquah forming an ad hoc Development of Tourism Committee, with Suther as the chair.

“We determined what we had that was tourism-worthy, and of course, the hatchery was on the list, and we developed a five-year plan,” Suther said. They got some money from the state to help promote tourism. Along the way, the small Salmon Days Festival, started in 1970 on the first weekend of October, became a Seafair-sanctioned event and started to bring tens of thousands of people to town. Salmon had become the city’s signature draw.

That’s why it was such a shock in 1992 when the headline in the Issaquah Press broke the news that the hatchery was slated for permanent closure, said Suther, who by then was serving as executive director of the Chamber,

The community quickly mobilized. Teacher Doug Emery, who taught his students about salmon by hatching eggs in a classroom aquarium, created a mural of the pictures and signs drawn by children to take to Olympia. Businessman Skip Rowley offered to fund buses to send school students to Olympia to testify. Issaquah Press Publisher Debbie Berto kept the issue at the top of the front page, and her editorials called for saving the hatchery. The tourism committee worked with 5th Legislative District Rep. Brian Thomas, who got money allocated for a study to determine what needed to be done to upgrade the aging hatchery. That study formed the foundation of the remodeling plan.

That effort spawned the formation of FISH, the non-profit Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery, with the mission of saving the hatchery and developing an educational program around the facility.

“The educational factor here at the hatchery is so basic to the whole protection of the world around us,” Suther said. “Learning about fish here has such a meaningful impact on the lives of students. It’s a magnificent story.”

She remembered that the Thomas Wittington Law Firm donated services to draw up and file the FISH incorporation papers. She and founding member Fred Kempe signed the incorporation certificate on Aug. 16, 1993. She credited Issaquah Mayor Rowan Hinds with suggesting the name for the new non-profit, creating the best acronym ever – FISH. She went on to serve on the FISH Board of Directors for many years and guide the organization through development of educational and volunteer programs and the remodeling project.

After 50 years of dedication to the hatchery, 85-year-old Suther still returns from her Bellevue home to volunteer with FISH at the annual celebration of Salmon Days. “I have such a sense of pride and ownership in this place.”

Saving the Hatchery Around the Corner: Debbie Berto

By Grace Reamer

When Debbie Berto learned about the proposed closure of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery, it hit a personal note for the publisher of The Issaquah Press. The historic hatchery was just around the corner from the weekly newspaper office. Just a few steps out of the back door and through a gap in the fence, the hatchery was literally in the backyard.

She vividly remembered that day in 1992 when editor Andrew McKean was going through the mail and came across a press release from the state Department of Fisheries about proposed budget cuts, including hatchery closures. One line buried in the notice would change the future of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery, as well as the entire community.

“It was 10 days before Salmon Days, the annual festival that regularly attracts 200,000 visitors to Issaquah to witness the salmon migration and celebrate the annual spawning season,” Berto said. “We came out with a front-page story right before Salmon Days, on Wednesday, with this screaming headline about the possible closure.”

In the Sept. 30 edition, just below the masthead, The Press announced in ominous bold letters, “Salmon Hatchery slated to close. Budget cuts responsible for probable closure next spring.” On page 4, Berto’s editorial implored, “Issaquah so far has only one aggressive economic development plan – tourism. At the head of the attractions list is the Washington State Salmon Hatchery. Now more than ever, its worth to the city must be recognized, and fought for.”

Below the editorial, Berto printed a petition and urged readers to sign on in support of keeping it open for the educational and economic value of the 1936 facility. A few days later, Issaquah Chamber of Commerce volunteers carried copies of the petition around during the Salmon Days Festival and collected signatures. Students of teacher Doug Emery, who had been hatching salmon eggs in a school aquarium, put up butcher paper on the hatchery fence and collected more signatures and pictures. Support soon coalesced around the educational aspect of the hatchery’s operations.

“The real shock is that the state fisheries staff has not bothered to consider the educational value of this interpretive center that is has worked hard to develop over the past 10 years,” Berto wrote. “The Issaquah hatchery is the closest one to a metropolitan area, and no doubt has the most visitors, from school groups and area families to international tourists.”

The community mobilized immediately. Just a week later, in a public hearing at South Seattle Community College, at least 70 students, business people, politicians and citizens flooded the fisheries staff with testimony about the hatchery, The Press reported. They delivered stacks of petitions and unrolled a huge sign full of student drawings and community messages. That grassroots movement was the beginning of a 30-year effort to create a center where salmon could teach a broad audience about environmental conservation. Berto and The Press were there the whole way, capturing the community’s rescue of the hatchery in gripping stories, photos and more editorials.

By then, Berto already was personally involved with salmon through her volunteer work with the city’s tourism committee. Years earlier, the committee was granted funding to bring in a speaker and put on a seminar for local business owners about how to “Seek Unique” and promote tourism, she said.

“It gave us the motivation, prioritizing what we’ve got,” she remembered. “The hatchery was high on the list, obviously.”

Berto and her husband, Tom Norton, volunteered to bring attention to the hatchery with some visual enhancements. “The first priority was to get the lobby fixed up,” with some signage and an aquarium showcasing salmon fry, she said.

She remembers their project to draw attention to the old round adult salmon pond, used to display salmon in the fall. During the off season, when the ponds were empty, Berto and Norton painted colorful stripes on the asphalt around the ponds, and then used a stencil to spray paint silver salmon on them. While the parents painted, their 2-year-old son played in the middle of the empty pond – and kept out of trouble.

As a newspaper publisher as well as a community volunteer, Berto had a unique perspective of the town’s values and resources. Fresh out of Central Washington University, and armed with degrees in journalism and sociology, she spent a legislative term working in communications for the House of Representatives in Olympia. There, she met Sen. John Murray, who happened to be the publisher of The Press at the time, and he steered her to a job in Issaquah in 1973. She spent nearly 41 years at The Press before retiring in 2014.

Along the way, she founded Issaquah Women Professionals in 1983 and also served as vice president of the Issaquah Chamber. She got involved with the Issaquah Kiwanis in 1987, the first year that they allowed women to join and is still a member. Her community leadership list is lengthy and she was named to the Issaquah Hall of Fame in 2013. She credits the town’s long-standing tradition of volunteerism with much of its success, including the rescue of the salmon hatchery.

Just as important was The Press coverage of the hatchery rescue efforts and then the formation of the non-profit Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery. She kept the story in the weekly headlines, and the community responded. The Press even printed the annual FISH reports about the number of volunteer tours provided and eggs collected at the hatchery each year.

“I always said, ‘The reason this town is so strong is that it has such a great newspaper,’” she recalled. Although The Press closed in 2017, another victim of declining print media revenue after 117 years in business, community volunteers still keep the hatchery running.

It was only natural that Berto would volunteer with the formation of FISH in 1993, and she served on the board of directors for 10 years. She even gave tours to school groups occasionally, as the buses unloaded just a few steps from her office. And she still maintains her membership to celebrate the program she helped build.

“Your heart can’t leave something that you’ve put your whole self into,” she says.

IHM: Issaquah Press Collection October 14, 1992: Page 2 (stparchive.com)

IHM: Issaquah Press Collection September 30, 1992: Page 1 (stparchive.com)

IHM: Issaquah Press Collection September 30, 1992: Page 4 (stparchive.com)

IHM: Issaquah Press Collection October 28, 1992: Page 3 (stparchive.com)

Spokesperson for Salmon: Randy Harrison

By Grace Reamer

When randy Harrison moved to Issaquah in 1989, it was a small, sleepy town in the hills east of Seattle, with just 6,700 residents. that was a big change for the guy from Orlando, moving all the way across the country with his family. but Issaquah offered something he couldn’t get just anywhere – quality of life.

the Issaquah salmon hatchery was a big part of that connection to community and the environment that Harrison sought. he took his kids to visit the hatchery soon after arriving, and they learned to appreciate the remarkable migration of the fish returning every fall.

Now 79, tall and lanky, Harrison made early connections with the natural environment working as a foreign correspondent in the 1980s for the Orlando sentinel. he wrote about war in Africa and Israeli patrols in Lebanon, and then he spent six months researching the destruction of rainforests around the world. summer vacations to hood canal (his then-wife was from Washington) were spent hiking at hurricane ridge and watching chum spawning in peninsula streams. the lure of the Puget Sound area was strong and they decided to relocate.

But journalism jobs locally were in short supply back then. after getting rejections from the Seattle times and Seattle P-I, Harrison found work with the Boeing co., and he soon moved into media relations and became a spokesman for Boeing. now retired, he still lives in the Squak mountain house on acreage filled with wildlife that the family bought when they arrived in town.

Always a fan of local news, he remembered reading in 1993 about the impending closure of the hatchery in the Issaquah press. he followed the story of the volunteers who lobbied in Olympia and successfully saved the hatchery. perhaps the most influential factor was the city of Issaquah’s pledge to spend $500,000 rebuilding the hatchery, he said. it was a huge sum for a small town to contribute toward a state-owned facility.

“The more i learned, the more wonderful – as in, full of wonder – it became,” he said. “you get your foot over the threshold and you get drawn into, “what can i do?’”

By 1995, Harrison was volunteering with the newly formed fish, after taking a class with a dozen or so other volunteers, including his neighbor, crash Nash. both of them soon were serving on the board of directors as well as leading tours for school students.

“One of the earliest recollections i have about the board was about messaging,” harrison said. “how many key messages can we have?” his experience with public relations helped the board narrow its focus down to, “this is the site of an annual miracle. we’ve altered the environment so completely, hatcheries are necessary, and here’s the reason why.”

“It wasn’t so much saving the hatchery,” he said, “but why does it matter? it was about the absolutely fundamental key role that salmon play in the entire environment.”

In his leadership role at Boeing, Harrison was able to enlist company support for fish in the form of a $25,000 grant to outfit the new theater with video equipment, cabinet, and benches. his legacy is the theater and its ongoing video presentation about the amazing salmon migration during spawning season, which helps turn the hatchery into a year-round educational facility.

He also advocated sharing the salmon story with students, and the addition of the salmon curriculum to the Issaquah school district’s elementary grades “may be one of the most underappreciated long-term benefits,” he said. The salmon in the classroom program that lets schools hatch salmon eggs in class and then release them in local streams, combined with fish’s salmon biology, lifecycle and habitat lessons, leaves a lasting impression on young people. those students then grow up to be the voters and leaders who will value the vital role of salmon in the environment.

“The mere act of witnessing this miracle has a transformative effect,” he observed.

One of Harrison’s most meaningful hatchery memories occurred during the annual salmon days festival, about 20 years ago. He was just walking onto the hatchery grounds, getting ready for his volunteer shift in the morning as early visitors were arriving. he spotted two young men in purple-and-gold University of Washington jerseys walking up to the bridge with a young woman between them. he heard her complaining loudly, “i can’t believe you dragged me out here just to see fish!”

Intrigued, harrison stood by to see her reaction. after looking over the bridge and into the chinook-filled waters of Issaquah creek, “she said, ‘do you mean all these fish are here to make babies and then die?’ they said, ‘yes,’ and she just burst into tears.”

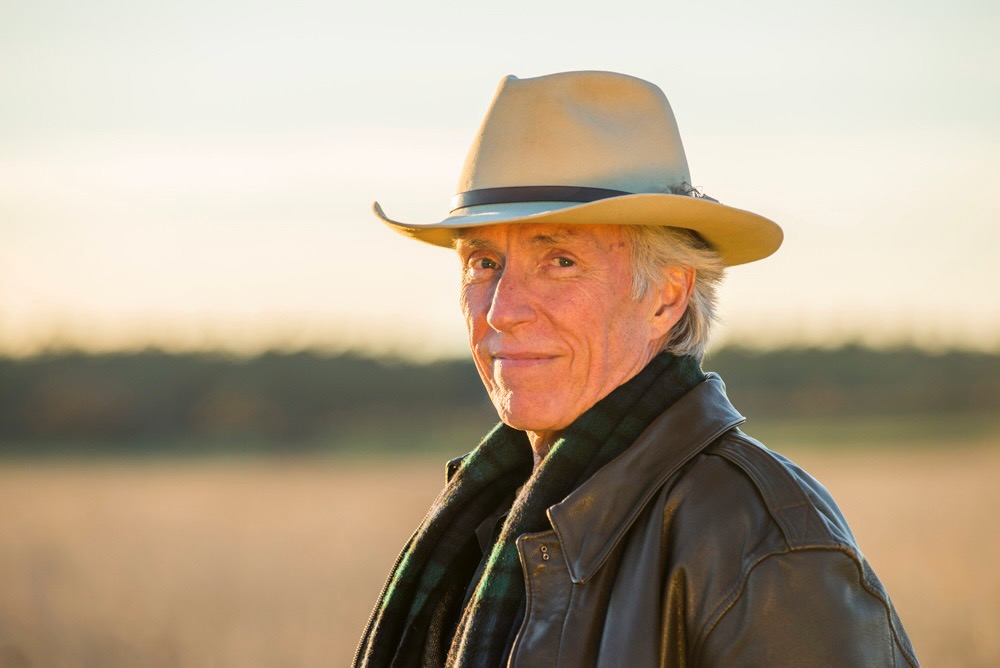

Two decades later, you can still find harrison hanging out on the bridge in his trademark hat, instilling visitors with a sense of wonder about salmon.

Buffalo Bill Conley: Salmon Planting Pioneer

It was a beautiful fall day at the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery when Bill Conley and his son backed up their pick-up truck to the adult holding pond, loaded a 300-gallon plastic tote in the back and started slinging fish. With several dozen adult coho splashing around in their spawning red and pink shades, they prepared for a grand experiment in salmon recovery.

The concept was to transplant the live fish, as they were ready to spawn, into a new stream, in the hope that they would lay their eggs in the foreign environment, even though the water did not match the smell of their home stream. But would the salmon go ahead with spawning? Or would they just head back downstream in search of the unique chemical signature that was imprinted in their brains as juveniles?

“Moving live adult salmon to another creek as a way of rehabilitating was on nobody’s radar when we did it,” Conley said. As a board member of Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery, he spent years of negotiating with the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, Muckleshoot Tribe, non-profit Trout Unlimited, King County and many officials to finally get approval for the transplanting experiment. “Everybody said it was a good idea.”

They started with Tibbetts Creek, located just west of Issaquah, and draining the valley between Squak and Cougar mountains before emptying into Lake Sammamish not far from the mouth of Issaquah Creek. Salmon migration up Tibbetts Creek had been severely limited by the 1940 construction of Interstate 90, which diverted the creek into a culvert under the freeway.

What they didn’t expect was the TV crew from KING-5 that just happened to be at the hatchery that day filming a story about the salmon spawning season, and they wanted to know about the truck loading up live coho. A school group touring the hatchery at the same time also was excited to learn about the transplanting project. They all followed the pickup full of fish over to Tibbetts Creek. But as a pioneering event, volunteers weren’t quite prepared for how to transfer fish from the truck on the road down to the creek.

“Fish were falling out of the nets and flopping around on the concrete,” Conley remembered. “And then all the kids were screaming and yelling.” But eventually, the fish all made it into the creek, and the whole operation was featured on the TV news that night.

Later, redd counts, fry trapping and marking with spaghetti tags all proved that the experiment at Tibbetts Creek was working. Since then, the adult salmon transplanting has been replicated on many other streams, including Little Spokane River, where Conley grew up. “It’s the coolest thing in my life,” he said.

Conley, known since high school as “Buffalo Bill,” moved west to Issaquah in 1983 to open a sporting goods store that bore his colorful nickname.

“The reason we moved here to Issaquah was because I was standing on the bridge at the hatchery with my son, looking down at the salmon, and he said, ‘Dad, we gotta move here,’” Conley recalled. Thanks to his new realtor and banker, Bob Catterall, Conley soon got involved with the Kiwanis Club. For decades, Issaquah’s business and civic leaders have got public projects done as volunteer Kiwanians.

Conley remembers well hearing the news of the impending closure of the hatchery in 1992. Kiwanis members soon mobilized to figure out what they could do to save the hatchery. Some called for the city or a non-profit to take over the hatchery from the state and continue operating it. City Administrator Leon Kos suggested that Kiwanis form an environmental committee to pursue hatchery solutions. Conley volunteered, along with Issaquah Press Publisher Debbie Berto, Issaquah Chamber of Commerce Director Suzanne Suther, and Issaquah City Councilmember Ava Frisinger.

That team put together an audacious proposal to the city council: contribute local taxpayer money to match state funding for updating and remodeling the hatchery. For a small town with fewer than 10,000 residents, offering to pay for refurbishing a state facility was unheard of, Conley said.

But it worked. The City of Issaquah pledged $500,000 to match state funding, thanks to the efforts of 5th Legislative District Rep. Brian Thomas. That $1 million was used to rebuild the fish-trapping weir across Issaquah Creek, allowing for fish passage past the hatchery. That was just the first step in the state’s commitment to spend another $6 million to rebuild and modernize the hatchery while preserving and restoring the original 1936 incubation building.

“It could not have been done without some flaming left-wing liberals there, as well as some real conservatives,” said Conley, who went on to win election and serve on the Issaquah City Council. “It was just a kick in the butt for me.”

In late 1993, the committee celebrated its success by recruiting a lawyer and drawing up incorporation papers for the non-profit Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery. As a founding member, Conley invited the group to meet upstairs at Buffalo Bill’s Sporting Goods, and after signing incorporation documents, they toasted with sparkling cider in champagne flutes.

Conley went on to lead student tours and coordinate volunteers for FISH as well as serving on the Board of Directors, before retiring and moving back to Spokane, but he continues to return to Issaquah every fall along with the salmon to celebrate the amazing migration. He credits the work of FISH with helping to change the public perception of hatcheries as part of the solution to dwindling salmon populations.

“The best way to get someone to care is to put a live adult salmon into a stream in their back yard,” he said. “That’s how you get people to become lifelong protectors of the environment.”

And if you ever ask Buffalo Bill what the best salmon is, you can be sure he will still give the best answer ever: “One on a grill.”

Brodie Antipa: Promoting Partnerships

The Issaquah Salmon Hatchery didn’t have much to recommend itself back in 1995, when Brodie Antipa first arrived. The aging incubation building needed a new roof and new equipment, and the old asphalt holding ponds were inefficient and difficult to manage adult spawning salmon.

“It was quite a bit more sterile than it is now,” with no signage or art or gardens or educational exhibits, Antipa said. “It was kind of dark and dreary.”

But change was starting. The old wooden weir – the fish passage barrier across Issaquah Creek – had just been replaced with a high-tech variable-height weir, thanks to matching funding from the City of Issaquah and the State of Washington. After it was threatened with closure, the hatchery was rescued through a community-wide lobbying effort to rebuild the facility as an education center. The first phase of the transformation had begun, and Antipa had been hand-picked to manage the hatchery and shepherd the next phases of the remodeling project.

“Mike Lewis had just left (as hatchery manager), and they knew what an important position it was,” with the new mission of the hatchery to deliver an environmental conservation message, Antipa said. “I knew how important it was going into it, and I knew that failure wasn’t an option. It didn’t take me long to realize that the hatchery was unique in many ways.”

At just 25 years old, Antipa was the new blood that the state Department of Fish and Wildlife sought to breathe new life into the 60-year-old hatchery. He practically grew up in the Fisheries Department, following the lead of his father, a state fisheries pathologist with a doctorate from the University of Washington.

Growing up in the Seattle and Olympia areas, “I always loved to be outside fishing and working with the fish,” Antipa remembered. Just like his father, he completed his fisheries degree at the UW, and immediately went to work as a biologist at the Cedar River Hatchery, where DFW’s sockeye program was just getting started. In fact, he continued his sockeye work on the Cedar part-time while managing the Issaquah hatchery.

He remembered being awe-struck by the huge support network he found surrounding the Issaquah hatchery – with city officials, state politicians, businesses, the Muckleshoot Tribe, non-profit organizations and community volunteers all working together to save and promote the hatchery.

“I don’t think of any other time in my career when I’ve seen such a collaboration,” Antipa said. “The volunteers were so awesome back then – a lot of laughter and a lot of smiles. We simply couldn’t do it at Issaquah without volunteers.”

He has fond memories of the volunteer business owners mobilized by Chamber of Commerce Director Suzanne Suther to plant flowers and spruce up garden beds at the hatchery. Issaquah Salmon Days Festival Director Robin Kelley always helped him get the hatchery ready for the annual festival that hosted up to 200,000 people on the first weekend in October.

He also credits Steve Bell, founder and first executive director of the non-profit Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery, for mentoring him, lobbying for grants and funding, and coordinating exhibit installations as well as the educational programming. Antipa learned to focus on the partnerships and the team effort that would make the hatchery and its messaging so successful, he said.

“We’ve known for a long time that hatcheries are necessary if you want to have cities and urban development,” Antipa said. But the state didn’t have a way to share that message with the public, until the proposal to use the Issaquah hatchery for outreach about environmental stewardship. “It was a real wake-up call for the department. Society has traded the habitat for development, and that’s the story that the hatchery can tell. Issaquah was really the first place to do it that I’m aware of in Washington.”

But it was a challenge. In the economic downturn of the mid-1990s, it wasn’t easy to justify the $6.5 million that the state eventually dedicated to three phases of redevelopment at the hatchery. The partnerships that Antipa and Bell cultivated kept the project moving forward, replacing the underground fish ladder with a longer ladder and underwater viewing windows. The old shallow holding ponds, where volunteers waded into the water with big nets to corral fish for harvesting eggs, were replaced with deeper ponds and automated crowders that improved fish survival. A new pedestrian bridge, twice as wide, was dropped into place by crane over Issaquah Creek, and new coho rearing ponds were dug on the south side. Best of all was the remodel of the historic incubation building, with its long row of windows and high-pitched roof, which got new equipment and roofing while maintaining the original appearance of the building.

“These old hatchery buildings just have a certain character that you can’t replace with a metal building,” Antipa said. “You almost feel a spirit within the building.”

In his nearly five years at the Issaquah hatchery, Antipa worked with the city on a partnership with the Darigold plant a few blocks away. That effort resulted in the installation of a waterline carrying pure well water that Darigold used to chill its butter to the hatchery, instead of just dumping it in the creek. At the hatchery, that pure water is mixed with creek water and used to incubate millions of salmon eggs, reducing the amount of sediment and pollutants bathing the incubation trays.

In 2000, Antipa was promoted to the complex management position for the Lake Washington drainage area, and then went on to serve as a hatchery reform coordinator. He’s now moved up to hatchery operations manager for all the facilities from Tokul Creek in Fall City down through the Green River system, where he works on reform efforts and changing policies based on new biological opinions and science.

So in 2020, it was Antipa who Kelley called in her new capacity as FISH’s executive director when the pandemic shut down public access to the hatchery. Because of the need for 24-hour on-call status for the three-person staff, complete closure was deemed necessary to reduce the risk of life-threatening illness. But Kelley proposed limited tours of small groups, with masking required, to meet the huge demand for safer, outdoor activities.

“This is going to be a hard sell,” Antipa told her. But his previous experience with the FISH organization assured him that they could do it safely, and he eventually got state permission for the tour program. “It took some time,” he said, “but Issaquah was then the only place in the state giving tours, and that was because of FISH.”

When he arrived nearly 30 years ago, FISH had a small core of volunteers helping with spawning and leading tours for students in the fall. Since then, with DFW support, FISH education programs have expanded to year-round, including spring science fairs and summer camps and a gift shop, along with a roster of more than 100 volunteers.

“I think there’s a huge value in what FISH has done to tell the story of salmon to the masses, to the people who wouldn’t normally hear it,” especially in how students learn about the links between salmon and their environment, Antipa said. “FISH is filling a niche and creating that value that wasn’t here before. You think about the magnitude and the number of people who have got exposure at the hatchery – it’s monumental. We can’t put a price on that.”

As the Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery prepares to celebrate its 30th anniversary, we are taking a look back at the people and the activities that brought about the formation and development of this unique organization and partnership.

A special thank you to Grace Reamer for telling FISH’s story, interviewing our key founders & writing these important historical & cultural stories.

Steve Bell: Forging FISHy Alliances

In 1992, as the State of Washington listed the Issaquah Salmon hatchery for closure, no one expected a community uprising of outrage. The sudden threat brought together a coalition of diverse people and interests, from real estate developers to environmentalists – factions accustomed to waging policy battles with one another rather than pitching for the same team. In the 5th Legislative District encompassing Issaquah, the Democratic senator and two Republican representatives agreed on very little, until the hatchery brought them together with a common cause.

“It is very rare that almost everyone in a community is sharing the same vision,” remembered Steve Bell, one of the founders and the first executive director of the non-profit Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery. “FISH was the opposite of polarization.”

Bell already had experience with public engagement through his service on the Issaquah Library Board, working on the effort to build a new King County Library in Issaquah, which now sits across Sunset Way from the hatchery. And then came four years of service on the Issaquah City Council, working on land use and groundwater issues and intergovernmental relations. Although the population of the town was less than 10,000, “Issaquah was always in a whirlwind of regional activities,” thanks to traffic woes in its crossroads location, Bell said. “It had big-city problems with a small-city budget.”

He already visited the hatchery often, thanks to its central location two blocks from City Hall and just a half-mile from his home. “I was fascinated by the salmon run,” Bell said. “It made Issaquah special and different.”

It also was the most-visited hatchery in the state, open to the public year-round, and the center of the annual Issaquah Salmon Days Festival. That’s why it came as a “total shock” when the state announced the impending closure of the hatchery due to budget cuts.

The dismay was immediate and galvanizing throughout the city, Bell said. The news was “like the evil lightning bolt with the stench of sulfur that came from Olympia,” and it felt “almost like Shakespearean betrayal.”

Along with city and county officials, business leaders, teachers and students, Bell jumped right into the letter-writing and testimony that eventually got a reprieve for the hatchery and funding for another year. That gave time to come up with a plan. By the summer of 1993, FISH was incorporated and the first board members were generating a multitude of ideas for sustaining the hatchery. But most of the board members were busy civic leaders who didn’t have time to track down funding sources or to fish for sponsors. Bell did have time, and he volunteered to take the lead on the efforts, putting his public service experience to work.

He admitted he had no experience with private fund-raising or with putting together the kind of coalition needed to turn around a state government bent on budget cuts. “But I knew there was all this positive energy,” and that inspired him to try something that hadn’t been done before with a hatchery in Washington. He pointed out that “the city was a little crazy about salmon. The Chamber of Commerce’s Salmon Days office had been doing wonderful, fun things for years celebrating the salmon – the Salmonchanted Evening dance, information volunteers call Salmbassadors. It was endlessly creative.”

Now retired and living in Arizona, Bell spoke by phone and reminisced about meeting with state lawmakers about how to add education to the core fish propagation mission, and by so doing, persuade the state to create a partnership unlike any other in Washington. Sen. Kathleen Drew pushed the concept of getting a commitment for matching funds, because “legislators wanted to be able to pitch this to their colleagues,” Bell said. He worked with city officials on a plan to commit up to $500,000 of city matching funds to badly needed renovations at the hatchery.

“The match was the big thing, and the council got widespread acceptance for that rather extraordinary allocation,” Bell said. “That was a risk for the councilmembers,” including hatchery champions Harris Atkins and Ava Frisinger. “They had to justify it.”

Next, he had many discussions with state Reps. Brian Thomas and Phil Dyer about the political process, and they outlined the “absolutely critical” importance of developing a facilities master plan, including cost estimates and timeline. They were able to get state funds allocated for the first part of a three-phase remodeling plan. Sen. Dino Rossi shepherded the final phase with a $3 million budget.

Eventually, the city and the county contributed funding to FISH to hire staff, and Bell was among at least 10 applicants for the executive director job. The board kept him on, and Bell quickly built a relationship with the Department of Fish and Wildlife staff.

“They (DFW) got religion about this working-with-the-community thing,” which was saving their facility and demonstrating how they were working with the community in a new way, Bell noted. They made space for him to move a desk into their hatchery office. But the busy office was not an ideal place to curry the favor of sponsors and donors, so FISH was granted the use of a fertilizer storage room in the hatchery garage. Bell had a desk and a phone and a portable space heater in the unheated room the size of a walk-in closet. Nonetheless, he said he was happy to have an office at all.

It was on the hatchery footbridge over the creek one day that Bell happened to meet Muckleshoot Tribe fish biologist Mike Mahovlich, who was watching the returning adult salmon. They quickly realized they had a shared interest in saving the hatchery, for education as well as fish production. “They have deep cultural reasons to try to maintain their fisheries,” Bell pointed out.

His efforts sent hundreds of letters to the governor from local officials, businesses, civic organizations such as Kiwanis, school district administrators, teachers and tribal officials. Most convincing, he said, were the letters and drawings from students, thanking FISH volunteers for teaching them about salmon and environmental conservation.

In his nine years leading FISH, Bell is proud of his work to incorporate educational exhibits on the hatchery grounds, as well as some unique art that is used for teaching. A giant mural depicting salmon predators and spawning now covers the curved walls of the water tower, designed and painted by local muralist Larry Kangas. In front of the incubation building is a pair of the most-photographed coho salmon in the state – the 8-foot-long bronze statues dubbed “Gilda and Finley.” The realistic sculptures were created by Chimacum artist Tom Jay, who also built an entire stream environment of plants, rocks, logs and gravel around the installation. Bell suggested the sculpture also could serve as a donation collection station, similar to Rachel the Pig at Pike Place Market. Jay agreed and installed a coin slot next to Finley’s dorsal fin. The cash, sometimes damp and moldy, poured in.

But even more than the thousands of dollars he raised and the political will that he fostered, Bell treasures the memories of students learning about salmon and their habitat – up close and personal. One day, he heard a tour of students screaming when a huge chinook salmon jumped out of the holding pond. Bell jumped into action, literally saving the salmon by wrestling the squirming fish back into the water. The kids cheered and Bell was a hero – at least for a moment.

“Yes, it was complicated at times,” said Bell, who moved to Portland and new challenges in 2002 after the hatchery remodel was completed. “But I had so many good people and good vibes and good ideas to work with. Everybody was activated about the project. There was all this positive momentum. Many, many people wanted to be part of something wonderful that was happening right in front of them.”